As my last post outlined, Cluster Pedagogy has three cornerstones: Interdisciplinarity, Project-Based Learning, and Open Education. For me, Open Education was the gateway principle that led me to the others. I was relatively unfamiliar with this concept when I arrived at my current teaching job, but fortunately the internationally renowned Open expert Dr. Robin DeRosa is the Director of the Open Learning and Teaching Collaborative at my institution. Within my first week on campus, she delivered a passionate presentation that started my journey out “into the Open.”

The approaches DeRosa presented opened my eyes to several ways in which traditional teaching methods - many of which I unknowingly still practice(d) - can limit accessibility to knowledge. Costly print textbooks are a barrier to many students’ education, so assigning Open Educational Resources that are freely available online can maximize student success. Moreover, inviting students to contribute to actual creation of such resources can empower them to shape the scholarly discourse on a topic rather than passively absorbing it. Such OEPs - or Open Education Practices - place students in charge of their own learning in what DeRosa calls a “Learner-Driven” model. To learn more, watch her “Introduction to Open Pedagogy” webinar co-presented with Rajiv Jhangiani, Special Advisor to the Provost at Kwantlen Polytechnic University, or check out the Open Pedagogy Notebook OER.

In Spring 2018 I first integrated OERs into my course Foundations of Art: Visual Culture by asking students to blog. Though blogging is hardly a radical pedagogical practice at this point, it radically changed my classroom. Students who had struggled with conventional short essay response during the previous semester were performing much better, and one who had even failed my fall Foundations course earned straight As throughout the spring.

Those ATI blues: Color coordinating with former PSU Academic Technologist Katie Martell...and the tablecloths. We were asked to introduce ourselves by drawing a portrait with some information about ourselves - including a hobby - then charting the connections we made with other attendees on an analog social networking board.

In May and December, I attended the University System of New Hampshire’s Academic Technology Institute as an Open Education Ambassador to explore ways I could build Open principles into my other courses. My project proposal? To co-create a textbook with my Contemporary Art Seminar. The fluid, ever-changing landscape of the contemporary art world poses major instructional challenges that textbook authors have yet to confront. First, traditional art history textbooks rely on a “canon,” a limited set of recognizable “masterpieces” that have withstood the test of time. However, the impossibility of gaining critical distance on recent art makes canonization impossible. More importantly, I want my students to challenge the very existence of a canon as a deeply flawed mechanism that imposes artificial order on unruly material, often to the exclusion of women and minority artists. Finally, contemporary art reflects multiple perspectives, but the available contemporary art textbooks are often written by a single author. Using a traditional textbook thus undermines the core philosophy of my courses, at great pedagogical and financial cost to my students. For more of my thoughts on this issue, check out my “Meet Your ATI Ambassadors” interview with Ryan French.

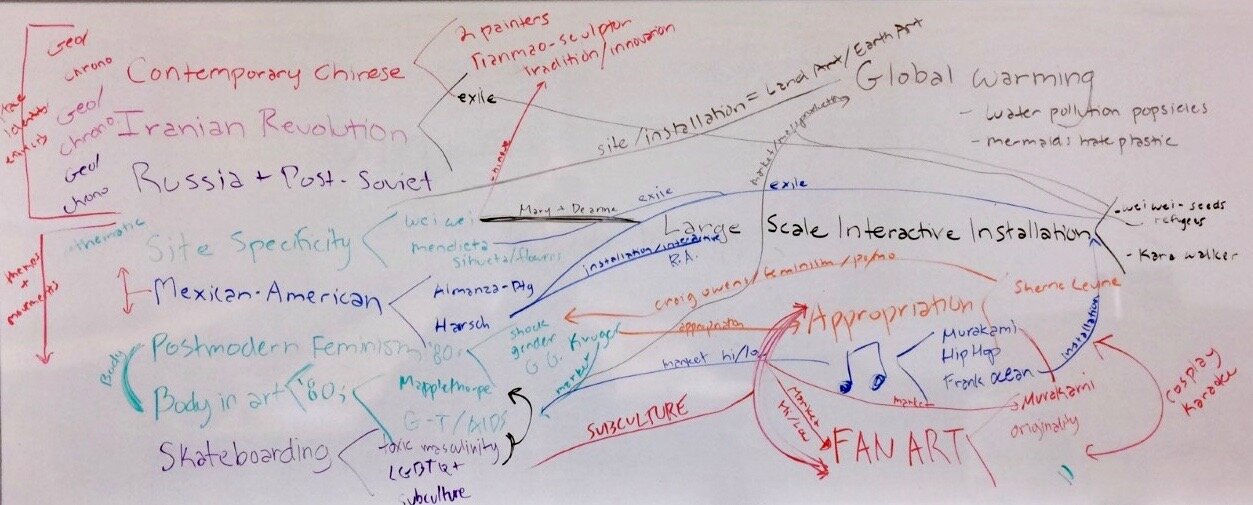

Last spring 2019 I put the plan into action, and collaborated with my students on a digital textbook of contemporary art that aims to account for the volatility and mutability of our subject matter. For the first step, they completed a Textbook Analysis paper that analyzed the structures and content of existing textbooks. They explained what was working for them and what was not. I was surprised by the acuity of their observations that unnecessary “filler” text wasted the time of both the reader and author, or that the elitist tone of a textbook could limit accessibility just as much as the textbook’s cost. Their next step was to author thematic or chronological texts that could serve as the introduction to a chapter, section, or subsection. In lieu of the paper sequence I normally assign, I had them craft entries on a two contemporary artist that related to their introductions to begin fleshing out a chapter. Here is their preliminary brainstorm of topics:

Contemporary Art Seminar students share some of their chapter ideas for the Opening Contemporary Art textbook. Their choices reframe the course content according to themes that reflect their own experiences of contemporaneity.

Some of the topics above provide the bread-and-butter topics essential to any discussion of art since 1980: site-specific art, appropriation, feminism and postmodernism. Others explore topics that professional art historians are just now starting to consider, like hardcore punk posters and “fan art.” Over the years, it is my hope that students can build and refine this archive. The result will be a mix-and-match Open Educational Resource that will allow me and other instructors to group different sets of artists into different thematic “chapters” based on changing contemporary needs. Such a customizable textbook would allow instructors to flexibly structure their courses thematically or chronologically, while enabling them to pick and choose the artists they deem most relevant at the time. In turn, these units can double as nodes that interface with potential projects in other disciplines: for example, one could craft a textbook on “Art and the Environment” by combining artist entries with relevant chapters from an OER Environmental Science textbook. On the last day of class, we charted some of these possible intersections and recombinations on the whiteboard:

You can see how the dense web of contemporary art may not lend itself to a linear print textbook!

This was definitely a pilot, with the attendant successes and failures. Here’s an overview of what worked well versus what I will do differently next time around:

What worked well:

H5P - H5P is an open-source program that allows you to create a broad range of digital interactive activities: maps, annotated videos and images, surveys, quizzes, sliders that can compare two overlapping images, and more. You should have seen my face when I first learned about everything H5P can do at our January ATI meeting - you would have thought I was watching an most exciting action movie rather than a presentation on academic technology! At first the students were understandably intimidated by the new tool, and we hit some snags figuring out how to actually add these activities into the textbook. But once we got the hang of it, H5P was surprisingly easy to use and generated some really thoughtful modules. Here are a few examples:

Here, Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ installation is meant to be participatory, as viewers are invited to take a piece of candy. A printed textbook image is static, but H5P allows student-readers to interact with the piece closer to how the artist intended through the joy of “picking” a piece of candy. For me, H5Ps are most successful when the “medium matches the message” as it does here.

Similar to the first H5P example, the “image slider” H5P option was carefully chosen to emphasize the student-reader’s understanding of the content. Being able to compare and contrast an artwork with its source helps students better understand the fine line between copying vs. reworking a source image in contemporary art.

This last example was made by an Art Education student, and I hope it’s something she could see herself using in her own pedagogy. This “annotated video” function has a lot of potential for online teaching at all levels.

As an educator myself, I saw three primary benefits of using H5P. First, the same students who struggled to articulate themselves in writing were able to better express their ideas by choosing from a wide range of H5P options. Also, many of my students are Art Education majors, and can create H5Ps to facilitate their own classroom teaching. Above all, the H5P additions to our textbook accommodate a wide range of learning styles in the OER spirit of accessibility.

Student Ownership - Much contemporary art is made to resisting static, oppressive institutions - political, economic, artistic. So once again, the medium of our Open textbook matched the message of the art discussed within because it, too, resisted the behemoth commercial textbook industries. We also debated whether it made sense for a professional art historian to determine what art and topics were “contemporary,” when they were arguable more removed from contemporary culture than the young artists in the class. The latitude to craft their own topics led to provocative new chapters never found in print textbooks, such as artist-musician collaborations and skateboard art. This seemed to create a sense of ownership in students, one of whom said this was the first writing assignment she’d wanted to share with her family and friends.

Areas for Improvement:

The OER Needs to be Central to the Course - I initially thought that I could swap out the independent research paper sequence I normally assign for textbook entries and continue to run class more or less normally. I was wrong. Even after devoting four or five full class periods to textbook support, the project still felt disconnected from what was happening in the classroom. I finally diagnosed the problem at the end of the semester when I learned the distinction between “project-oriented” and “project-based” learning from Brandon Haas’ and Elisabeth Johnston’s primer on experiential learning. The former asks students to apply content or skills they’ve already learned to complete a project afterward. Project-based learning, however, centers the project itself and teaches content and skills through the project. Next time, I’ll make the textbook a core of the curriculum.

More Discussion and Collaboration - This dovetails with my observation above that the project needs to be the centerpiece of the class. The days where students discussed the results of their Textbook Analyses and the connections between their topics (imaged above) were really exciting! Even those days where students simply worked on writing their independent entries alongside one another in the classroom gave us the physical connection necessary to feel like true co-authors. We needed more of this.

More Guidance for Topic Selection - The whole point of Open Pedagogy is student agency, so from the outset I thought it was important for students to choose their own topics. Exactly as I’d hoped, this generated cutting-edge original scholarship on topics such as the aforementioned artist-musician collaborations and skateboard art. However, the innovative young scholars who proposed these ideas were essentially punished for their bravery by having to hunt harder for accessible, quality resources. This created some workload equity between students who chose well-trodden terrain and those who to probe harder to find information on under-researched topics. Next time around, I’ll offer a list of options for students to choose from while also welcoming ambitious students to choose their own, with the caveat that a new topics require more original research and critical analysis. With any open class, an important challenge is to find a balance between openness and structure so the students have both support and choice.

In the spirit of Open, I’m sharing the OER resources I created for this activity:

I hope you learn from our experiences and continue to follow Opening Contemporary Art as it evolves next semester!

Sarah