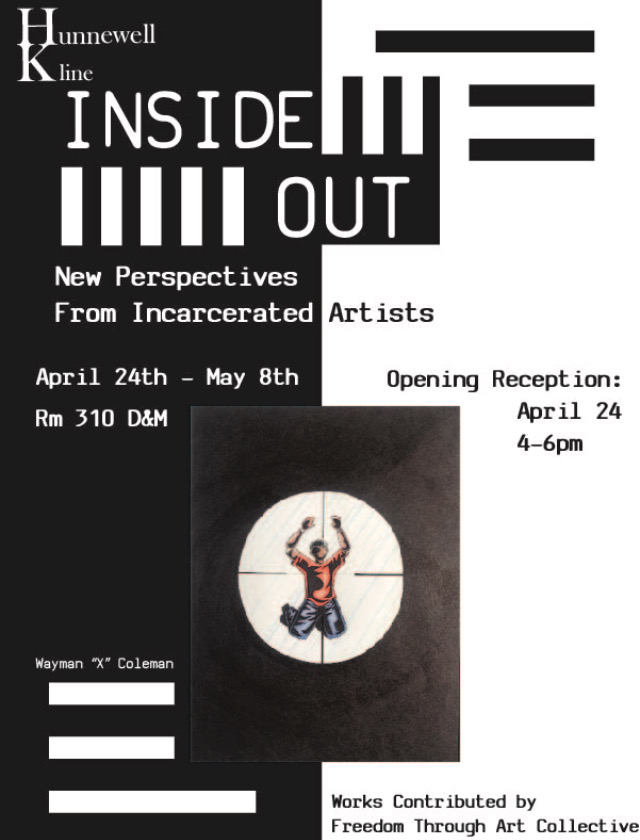

One April evening in April 2019, I found myself engulfed by a sea of interacting faces. One-hundred and fourteen of these faces belonged to thoughtful and smiling guests at the opening reception of the exhibition Inside/Out: New Perspectives from Incarcerated Artists. Ten of the faces were those of the student-curators, shimmering with nerves but beaming with pride. The rest of the faces encircling the room were present by proxy of powerful portraits rendered in colored pencil — drawings by artists who were currently serving time in prisons nationwide.

What was the process that brought all these faces together? The exhibition opening was the culminating public event for the course The Museum as Medium: Exhibiting Culture on Campus. The course description describes this class as follows: “[students] will draw upon their interdisciplinary knowledge to establish all aspects of Plymouth State University’s new Art History Teaching gallery according to their collective vision. Students are encouraged to respond to the challenges facing galleries today by experimenting with the space's mission, format, and operations.” In this post, I aim to explain the institutional setting that enabled me to develop this course, and how it addressed current pedagogical trends toward Open, Interdisciplinary, and Project-Based Learning.

Genesis of the Course

When I arrived on campus in 2017, Art History inherited a large windowless room that had formerly served as a slide library. Towers of metal slide drawers and projection equipment were stacked throughout the room, shelves of outdated survey textbooks lined the walls, and colleagues had begun using the room to store their retired “sad chairs of academia” and other unloved furnishings. The before and after below shows how messy the space still was, even after I’d already cleared out said sad chairs! My vision to repurpose this space as a gallery coincided with the closing of another campus gallery space on the first floor, so we were able to reclaim the wood floors and lighting to create an extra-swanky space.

From the beginning, wanted to use this space to honor emeritus professors Dick Hunnewell and Naomi Kline, who had spent decades in this room crafting their art history lectures. As Hunnewell observed at the opening, the physical transformation of the space reifies broader changes in art history pedagogy. The conversion of the space from a place where slide lectures were assembled to a space where students can curate their own shows and projects reflects a shift in the field from slides and surveys to projects and themes.

Now that we had a gallery site, I needed the students activate it within the Art History curriculum. Museum studies courses are standard fare in art history programs across the country, and it’s not uncommon for them to include hands-on curatorial projects. What distinguished this spring’s offering was that our students were not creating an exhibition or initiative for an existing or imaginary space – they were shaping the space itself. So while conventional exhibition assignments do touch on multiple areas of cultural work – budgeting, installation, object selection – this class asked them to consider these issues from a broader institutional perspective. They couldn’t simply worry about their own exhibition budget; they also needed to consider how this budget fit into our larger operations, and how we could sustain this for the future. Likewise, they needed to make more than a narrative for a single exhibition; they were required to think about the entire mission of the gallery and its role in the larger campus and regional art scene.

What’s an INCAP?

Students in INCAP courses complete their projects collaboratively: “the project is large and complex enough that it requires input and work from more than one person to be successful.”

This course was part of a pilot program for a new type of General Education course at Plymouth State University, the Integrated Capstone (INCAP). Coming toward the end of a student’s progression through the General Education program, the INCAP asks students to draw on their knowledge gained from previous Gen Ed and major classes in order to “collaborate across disciplines to create signature projects that address a significant problem, issue, or question.” By PSU’s definition, a signature project:

Is transdisciplinary: The project integrates knowledge from multiple disciplines and sources to create something new that could not be created without all of them.

Is completed collaboratively: The project is large and complex enough that it requires input and work from more than one person to be successful.

Is student-driven: While faculty, staff, and community partners provide guidance and coaching, student agency and independence move the project forward.

Requires metacognitive reflection: Students reflect on what and how they learn and how their learned knowledge, skills, and dispositions might be transferable to other contexts.

Reaches beyond the walls of the classroom: The work of the project touches the world outside the classroom in some way.

Has an external audience for project results: The results of the project are presented to someone who is outside of the class.

Is completed ethically and respectfully: Work on the project engages internal/external audiences and/or partners with mutual benefit.

I knew that my planned museum studies course was going to complete check all these boxes, but at first I was unsure whether the topic – museum studies – was too narrow for the INCAP as we defined it. Yes, I was giving my students an almost excessive amount latitude in how they chose to shape the space. But was it too limiting to ask them to work within a defined site on campus?

The way I see it, there are at least two different ways of defining an INCAP section “topic.” The first is to “theme” the course around a specific issue, question, or area of knowledge. Examples from the pilot include:

· “One Small Step: Marking the 50th Anniversary of the Moon Landing

· American Food Issues: From Fast-Food Nation to Farmstands

· Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Dao

· Sustainable Innovation in Public Health

Topical courses gives students total latitude to define the project in any way they choose. For example, students in Abby Goode’s American Food Issues section approached the course’s core issues through projects as different as measuring food waste in the cafeteria to rebranding the student food pantry as a less-stigmatizing nutrition center. Conversely, in my class the project was far more defined – if students wanted to, say, launch a model rocket, that would hardly be appropriate! But they had much more freedom to choose on any topic they wished, and indeed, students proposed exhibitions on wide-ranging themes such as environmental advocacy, Instagram art, virtual reality, and New Hampshire women artists. For me, it’s equally valid to structure the class around a theme or an approach, but the question of how much structure – and what kind of structure – is enough to “theme" a class is a major conversation surrounding all student-driven projects on our campus.

Cluster Pedagogy: Open, Interdisciplinary, and Project-Based Learning

You’ll remember from my last post that PSU’s Cluster Learning model has three nodes: Project-Based Learning, Open Education, and Interdisciplinary Inquiry. Here are some musings on how each interrelated pedagogical technique moved our work forward. A common theme in my experience of all three areas was my feeling that I was “doing it wrong,” mostly because I was comparing my own experience with clichés and misconceptions about what good pedagogy should look like. Trying new things can take both professors and students out of their comfort zones!

Project-Based Learning

Active learning doesn’t always look this hands-on, but it did when we were renovating our gallery space!

I joined the faculty running the sections noted above in a fellowship cohort. We met monthly in a reflective practice group to share and learn from our challenges and successes. When it was my turn to present midway through the semester, I made a confession: I thought I was “doing it wrong”! What was happening in my classroom didn’t look like the stock-photos accompanying the many pedagogy articles I had read. No one had hammers in their hands. They weren’t huddled in a circle wearing goggles and smiling over a chart. And they certainly weren’t standing on tables shouting “oh captain, my captain!” Was what we were doing actually Project-Based, then? Was it Open? Was it interdisciplinary?

Despite having a PhD in interpreting images, I had completely misread the visual of what was happening the room. The very next class, we had a guest curator speak with us. The first question a student posed to her was: “What makes something a gallery? Is it the physical space, or is it more of an idea?” The depth of this question made me realize that while my students had looked physically passive at their desks, their minds were actively engaged in critical work on their project. This was an important lesson: project-based and active learning can look different ways, and often doesn’t appear as flashy as we like to tell ourselves. My quiet, methodical class was in fact engaging in what Goode calls “slow interdisciplinarity,” working thoughtfully through the project on their own terms. That said, I think the students may have also internalized this preconception about how project-based learning should look. Because when the tools did come out, the first thing they wanted to do was pose with them — see the action shot above!

Overall, in terms of Project-Based Learning I felt this course was much more successful than my concurrent Opening Contemporary Art initiative because the project was a central driver of everything we did.

Open Education

Posing with DeWitt Godfrey’s steel sculpture on our field trip to deCordova Sculpture Park + Museum, this photo could be seen as a metaphor for how each student’s individual contribution supported the overall project. And also possibly an album for a 90s rock band.

The calm and quiet class dynamic didn’t last long, because project-based learning tends to bring students together! Soon we shared suite of inside jokes about early 2000s music, luxury skincare brands, and getting adopted by the rich folks whose fancy driveway we used to pull a u-turn in our field trip van. Getting to this point was one of the biggest challenges of the class, both for me and the students.

I wanted my classroom to be Open, so I encouraged the students to organically choose the structure and composition of their own working groups. Some of my colleagues also took this approach, whereas others sorted the students themselves using various strategies. Once again, I thought I was “doing it wrong” because my students just wouldn’t split up into groups. Wouldn’t it be productive to have a finance group, a curatorial group, and a marketing group, I suggested? But I later realized was inadvertently imposing my own professional knowledge about how museums are normally divided into departments. Why couldn’t our gallery have a flatter, more collaborative administration where everyone contributed to every decision? The students had inadvertently addressed a major controversies in museums today: the hierarchical power dynamics among staff, collectors, and artists. Everyone said they did not want to divide up because they wanted exposure to the widest range of experiences, and it wasn’t until the end of the semester when the needs of our project timeline necessitated them to divide into a Writing Team and a Graphics Team.

“Open” was not just a way of executing our project, but also a primary theme in the project itself. The whole idea of Open Pedagogy was starkly contrasted with the experience of our collaborators, incarcerated artists whose lives were the opposite of “open.” Agency thus became a theme of the exhibition as well as the structure of the INCAP.

Interdisciplinary Inquiry

Picking up Artwork from the Freedom through Art Collective.

Interdisciplinarity was key to exploring this issue of agency in an ethical, authentic way. The goal of the show – bringing visibility to incarcerated artists – was inspired by one student’s Women in Crime class that she was taking through the Criminal Justice department. This was her first class in that field, and none of us – myself included! – knew much about the penal system. We soon found ourselves tripping over our words. Do we call the artists criminals or inmates? Is there a more PC word for cell? And how do we balance our desire to humanize the artists without glorifying them at the expense of their victims? CJ Professor Kate Elvey came to class to share her expertise and talk through these issues with us. We partnered with the Freedom Through Art Collective to learn more about the ethics of displaying work by incarcerated artists, and they became external partners who lent us the work for our exhibition.

Simultaneously exposed to Criminal Justice and Art Historical ideas, students drew fascinating parallels between prisons and art museums. Whereas the small, windowless gallery originally posed spatial challenges, one student remarked that it actually echoed the feeling of being enclosed in a cell. We read Brian O’Doherty’s classic text “Inside The White Cube” and learned how the white walls of art galleries are used to support existing power structures, which invited parallels with prison architecture. And when we laid out our gallery guestbook before the opening, it felt eerily reminiscent of a prison’s visitor log. I’ve recorded some of the student’s other gems of curatorial wisdom in this video walkthrough:

Interdisciplinarity was important not only in the content of the show, but also in our methods of creating it. The student evaluations suggest they perceived themselves as a very interdisciplinary group even though those disciplines were closely adjacent: studio art, graphic design, art history, anthropology, and education. Each class member brought slightly different expertise to the table to design a logo, set up our social media, and so forth. Perhaps the best example of this is how our education major organized a station for visitors to send feedback to the incarcerated artists, adding an interactive educational element to the display.

A goal of the INCAP is for everyone to bring their own disciplinary expertise to the table in this way. However, with my students I actually saw disciplinary knowledge flowing in the opposite direction: students were forced to step outside their majors in order to solve project-related problems. Individuals who would normally be intimidated by a budget, uninterested in the prison system, or too intellectual to pick up a paint roller were motivated to enter these new fields and learn the new skills necessary to complete their projects.

Graphic design students brought their expertise to bear on our provocative press materials.

Outcomes and Next Steps

Let’s go back to the scene I set at the beginning of this post. I can’t say this in a less cheesy way: my heart was about to explode with pride for what my students had accomplished. While briefly thanking our 100+ guests, I talked about how the students worked together collaboratively as a single, non-hierarchical, leaderless group. What if every institution could work this way? Our government, our schools, our galleries, our prisons? It struck me that this generation of students would be the leaders of such organizations when my own unborn baby was growing up, and it gives me so much hope for her future that young people are thinking differently about their institutions rather than passively accepting the status quo.

Many students reported that what they’d done didn’t “click” until they were able to talk about it with people who attended. As educators we often talk about the educational process being more important than the product, but in this case the public-facing, non-disposable result was vital. One student reflected:

“[A] professor [at the opening] wanted to know why our exhibit did not focused [sic] on the crimes these artist[s] had committed. I explained that many of these artist[s] had quotes that talked about making artwork while incarcerated and focused on how important it was to them. For our class it was not about what they had done to be in prison but rather we wanted to focus on how creating artwork is so essential to these prisoners. We wanted to look at them for the artist[s] they are and what drives them to make art and not to belittle their work by pointing out the wrongs they have made in life. At the end of the conversation I had with the professor I am not sure she agreed with our ideas but I think this was an important part of our exhibit.”

Another wrote:

"In our second reading post, it was said that the materiality of museums as buildings, coupled with the materiality of their collections, is important for what was called the ‘objectification’ of culture. It turns culture and identity into a “thing.”’ Presenting culture and identity in this way naturalizes them, makes them seem mere matters of fact. Once we decided that we wanted to obtain work from incarcerated artists, I wanted to make sure that their work was expressed in a fair manner. It was important to me that we were not objectifying the inmates. I thought about whether or not we would be helping them or harming them. It made me wondered whether or not these artists would be immediately prosecuted. I did not want to tell people that would be visiting the galley why these people were locked away. It was important to ensure that viewers felt a connection and the right connection. The artists wanted to be seen as normal human beings trying to make the right decisions in life. Not many of them are. That is why I love Freedom Through the Art Collective. It gives prisoners a chance to be treated like humans who are praised for their talents rather than being rejected for their mistakes."

If a goal of the INCAP is to “touch the world outside the classroom in some way,” these students’ work went even further to reach into the closed-off, often-invisible world of the prison system. In a previous Museum Studies course I might have simply assigned readings on diversity and empathy – but through project-based learning, the students actually fostered diversity and empathy in a cultural space. They repeatedly said “I just got chills!” at various stages of project development, suggesting the outcomes were visceral and embodied rather than simply intellectual.

The entire team poses at the opening with Art History Emeritus Professors and project namesakes Dick Hunnewell and Naomi Kline (back row center).

Of course, the class wasn’t perfect. The short length of the semester gave us little time to assess and reflect on what was happening as we went along, and we were lucky our external partners were willing to work with our unreasonable timeline. We also became so focused on the exhibition at hand that certain gallery operations were overlooked. Above all, the next round of students will need to put more thought into how we can keep the gallery sustainable even in the “off-season” when an INCAP class is not running.

In my next post, I’ll share some tips I learned at last summer’s Institute on Project-Based Learning at Worcester Polytechnic Institute that might help me — and hopefully you as well — weather these challenges more smoothly. But in the meantime, I’m embarking on the ultimate “project-based learning” experiment – having a baby!

Sarah